© picture alliance / AA | Muhammed Enes Yildirim

© picture alliance / AA | Muhammed Enes Yildirim

Yaşar Aydin, Jens Bastian and Maximiliane Schneider

Special thanks to Anton Delchmann, Daniel Kettner and Michael Westrich

October 23, 2024

1. Introduction

2. Bilateral Relations: Political and Institutional Framework

3. Germany and Turkey: An Economic Comparison

4. Sectoral Characteristics of the Turkish Economy

5. Germany – Turkey Trade Relations

6. Transnational Relations

Germany and Turkey have strong economic ties, including in trade, investment and tourism. Companies from both countries have a significant presence in various sectors, including those for manufacturing, textiles and automobiles. Against this backdrop, we argue that, due to growing trade and investment levels, bilateral political and economic cooperation has considerable upward potential.

Germany and Turkey have a long-standing and multi-faceted relationship that involves the respective economies, politics, security and culture. Germany is also an indispensable partner for Turkey’s relations with the European Union (EU). These bilateral relations also have a strong transnational dimension, namely a large (labour) migrant community in Germany and significant mobility – for example with tourism and the exchange of expatriates – between the two countries. Nevertheless, the respective economies – and trade in particular – form the main pillar of the bilateral relationship, which has survived and overcome numerous diplomatic tensions and interstate differences on geopolitical issues.

Germany and Turkey have highly diverse political, economic and social structures. But they are more closely intertwined than any other two states in Europe, even though they do not share borders. Since the 19th century, Germany and Turkey have not only engaged in commerce, but also collaborated politically and militarily (see the chrononogy below).

In the following, an overview of economic relations between Germany and Turkey is provided while including the political and institutional framework as well as demographic and socio-cultural dimensions. This serves not only to highlight the depth of and prospects for cooperation, but also to demonstrate where and why the potential in the bilateral relationship is being under-utilised. Empirically, the analysis is mainly based on primary data sources, which are listed in detail below the figures. In addition, the various topics discussed draw on a growing body of academic and grey literature on the subject.

First, the political and institutional framework of bilateral economic relations between Germany and Turkey are outlined. Second, it compares the countries on key economic aspects such as gross domestic product (GDP), GDP growth, population projections and demographic factors. Third, we outline the characteristics of the Turkish and German economies, as these guide companies from both countries in their investment decisions. Fourth, trade relations between Germany and Turkey are described, and the importance of transnational relations for economic cooperation are highlighted. Finally, transnational relations between Germany and Turkey are presented.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1924 | German-Turkish Treaty of Friendship |

| 1927 | German-Turkish trade agreement |

| 1961 | Agreement on the recruitment of Turkish workers for the German labour market (‘Anwerbeabkommen’) |

| 1996 | EU-Turkey Customs Union |

| 1999 | Candidate status for Turkey at the EU summit in Helsinki |

| 2005 | EU accession talks with Turkey |

| 2012 | German–Turkish Energy Forum |

| 2013 | German–Turkish Joint Economic and Trade Commission (JETCO) |

| 2016 | EU-Turkey Refugee Agreement |

| 2021 | Ratification of the Paris Climate Agreement by Turkey |

Sources: Deutscher Bundestag, »Zur Geschichte der deutsch-türkischen Beziehungen 1918 bis 1998«, (Wissenschaftliche Dienste)

↑ To the Table of Contents

After the end of the Second World War, bilateral relations between Germany and Turkey rapidly intensified, following the resumption of diplomatic relations in the early 1950s. As a Cold War flank state of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Turkey – a member since 1952 – contributed to (West) Germany’s security umbrella, while the Federal Republic assisted with the modernisation of Turkey’s armed forces and Ankara’s bid to join the European Economic Union. Through NATO membership, Germany and Turkey are allies that cooperate closely on military, security and intelligence matters, for example the European Sky Shield.

The bilateral labour recruitment agreement between Ankara and Bonn (1961) helped West Germany meet its labour needs in the midst of the post-war economic miracle (Wirtschaftswunder), and it provided Turkey some relief regarding unemployment levels and assisted with meeting its foreign exchange needs through the remittance of so-called guest workers (Gastarbeiter). The guest worker community has given rise to a transnational diaspora that has been a political factor for Germany and provided a strong bridge between Germany and Turkey.

The relationship between Germany and Turkey is framed by a number of international institutions and organisations. Both countries are members of the United Nations (UN), the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, the World Health Organization, and the Council of Europe and NATO. Turkey is a candidate country for EU membership and is part of the EU’s single market through the Customs Union (CU).

Germany played a pivotal role in Turkey’s accession to the CU (1995) by elevating Turkey to the status of an EU candidate state (1999) and initiating the accession negotiations between Brussels and Ankara (2005).

Over the past decades, German and Turkish companies have engaged in extensive business exchanges, reflected in the steady expansion of bilateral trade, investment relations and transnational people-to-people interactions. Numerous large German companies such as Siemens, AEG, Mercedes Benz, Hugo Boss, Tui and SunExpress, among others, have had long-standing corporate representation and facilities in Turkey, while Turkish companies such as Egetürk, Turkish Airlines, Gazi and numerous family-operated retail shops and restaurants have made lasting impacts on the German economy.

German and Turkish companies have also established a number of institutional cooperation formats in recent years. These platforms for bilateral cooperation are designed to expand the scope of bilateral trade and investment relations. To illustrate, the German-Turkish Joint Economic and Trade Commission (JETCO) was established in 2013 as a cross-industry platform. Its objective is to reinforce bilateral collaboration, particularly in the domains of trade, industrial cooperation, tourism and infrastructure. An annual meeting is held as part of this cooperation format, most recently in October 2023 in Ankara during the visit of the Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection, Robert Habeck.

The German-Turkish Energy Forum, established in 2012, is another project collaboration. The forum serves as a central platform for energy policy dialogue between the governments and businesses of both countries. The Energy Forum’s focus is on renewable energies, energy efficiency, electricity distribution and transmission grids. Germany is providing financial assistance to Turkey in the form of loans, which are part of the investment subsidies from the International Climate Initiative (IKI). These credit lines are being implemented by the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) in cooperation with the Turkish Central Bank (TC Merkez Bankası).

↑ To the Table of Contents

Germany is the world’s fourth-largest economy in terms of GDP, while Turkey currently ranks 19th. Turkey has enjoyed relatively high GDP growth in recent years, as reflected in Figure 1.

In contrast to Turkey, Germany has a high savings rate. According to Eurostat, the statistical office of the EU, the gross savings rate of private households in Germany was 19.9 per cent in 2022, while in Turkey, it was just 10.5 per cent, based on data from TurkStat. As a result, Turkey is forced to resort to external financial resources in order to make the necessary investments, as savings are not sufficient (Euro News, 2023).

Despite the necessity for Germany to reinforce its digital sovereignty in order to become a formidable digital powerhouse, it continues to act as a technology provider for Turkey (KfW Research, 2021; Campanile, 2024).

Fig. 1: Real GDP growth

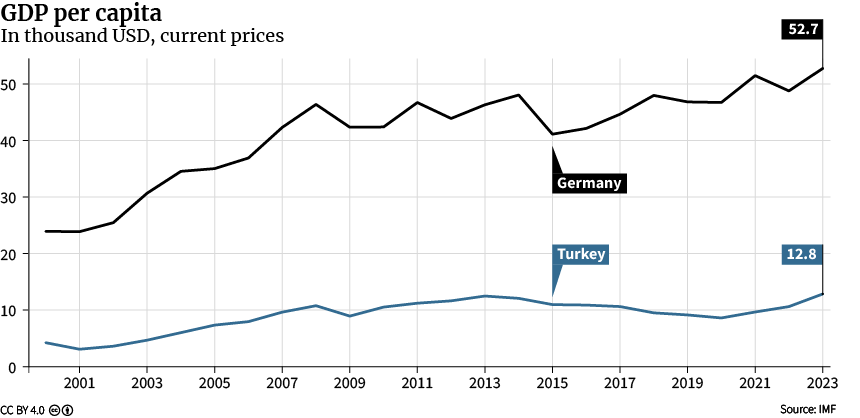

Although Germany’s growth rate has been lower in recent decades (see Figure 1), its GDP and GDP per capita are more than four times Turkey’s (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2: GDP per capita

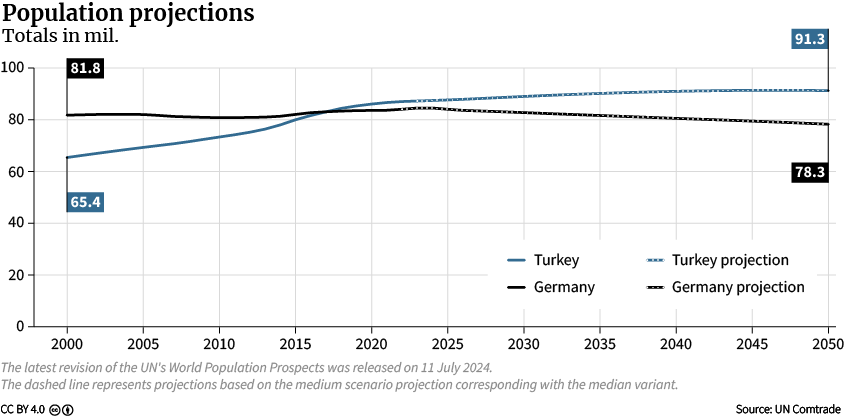

Geographically, Turkey is more than twice the size of Germany. It has a younger and larger population than Germany – 85 million citizens compared to 83.8 million. This provides German companies with a large domestic export market and manufacturing opportunities.

The population projections in Figure 3 are based on data from the UN Population Division. They underscore that the inflection point in population growth between Germany and Turkey is in 2016. This disparity of further growth in Turkey and decline in Germany is projected to continue until around 2048.

Fig. 3: Population projections

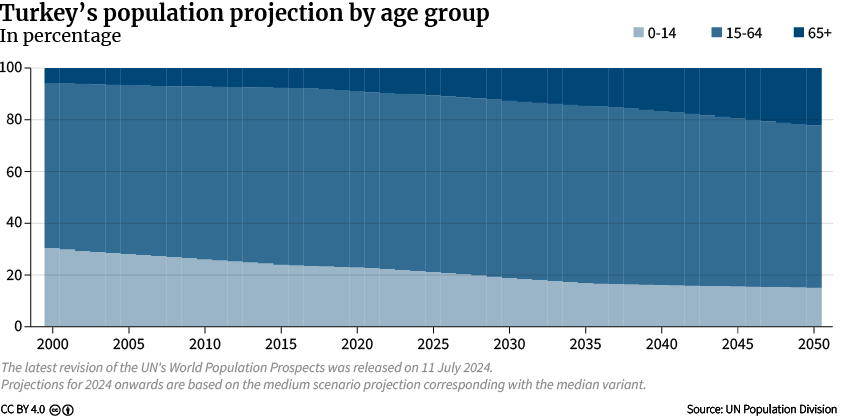

The Turkish economy is characterised by a number of demographic factors that are highly critical for German companies when making investment decisions: Based on current projections, Turkey will have the second-largest population in Europe by 2050, coming after Russia and before Germany. Contrary to most European economies, the working-age population is projected to grow until the late 2030s (Figure 4).

Fig. 4: Turkey’s population by age group

Furthermore, the Turkish population is young when compared to European countries. In 2023, those aged 14 and under constituted approximately 23 per cent of the total population (Figure 4). Also, in 2023 Turkey registered the lowest labour force participation rate of all countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) reported for October 2023 a labour force participation rate of 53.1 per cent, compared to the OECD average of more than 70 per cent.

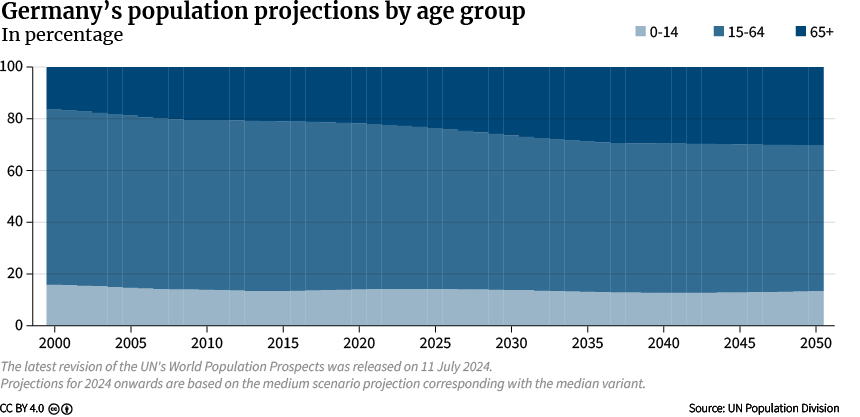

Fig. 5: Germany’s population projections by age group

Turkey’s geographical location at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and Africa makes it a bridging corridor for gas and oil, a hub for land-based and maritime transport routes, and a springboard to emerging markets. Apart from demography and market size, there are additional structural factors that explain the attractiveness of Turkey for German companies.

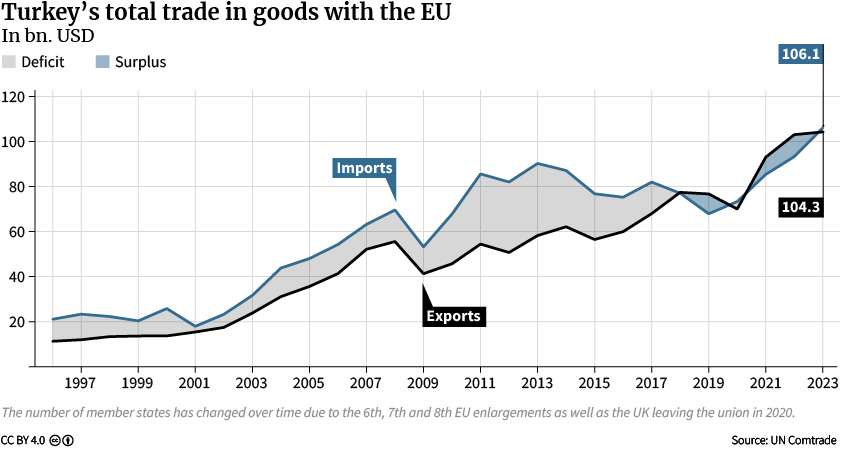

First of all, the main product lines of the Turkish export economy are characterised by medium-value added manufactured goods such as automobiles, machinery, textiles and clothing (leather). Second, Turkey is a supplier of services and mainly reliant on tourism and the financial sector (banking and insurance). Moreover, the EU is Turkey’s largest export market. As Figure 6 illustrates, Turkey’s total trade in goods with the EU has remained nearly in balance since 2017.

The EU-Turkey CU is a central catalyst for bilateral trade between Germany and Turkey, whose total trade in goods with the EU reached USD 210.4 billion in 2023 (see Figure 6), which corresponded to a third of Turkey’s total trade volume of USD 617.2 billion. The EU is Turkey’s single-largest trade partner: 40 per cent of Turkey’s exports go to the EU, while 25 per cent of Turkey’s imports come from the EU.

Fig. 6: Turkey’s total trade in goods with the EU

EU trade with Turkey can further expand if and when ongoing negotiations about a modernisation of the CU bear fruit. This expansion would include sectors such as services (finance and insurance) and unprocessed agricultural products. The CU brought significant growth and welfare gains to Turkey and countries in the CU. There are also geopolitical implications to consider: A modernised CU would further strengthen EU–Turkey as well as Germany–Turkey (economic and political) relations. In the absence of such a modernisation, other countries such as Russia (e.g. Rosatom) and China (e.g. BYD) are expanding their footprints in Turkey.

As a result of the economic growth in recent decades, regional differences between east and west as well as north and south have narrowed in terms of the economy, social standards and infrastructure. With regard to regional diversity, all of the major cities in the western and southern parts of Turkey are expected to grow in terms of population. In prosperous industrial centres such as Bursa, Konya, Kayseri, Gaziantep and Antalya, further industrialisation and economic growth are expected. Therefore, these cities will experience strong population growth due to new waves of migration, especially from the surrounding hinterlands and due to refugee arrivals or relocations.

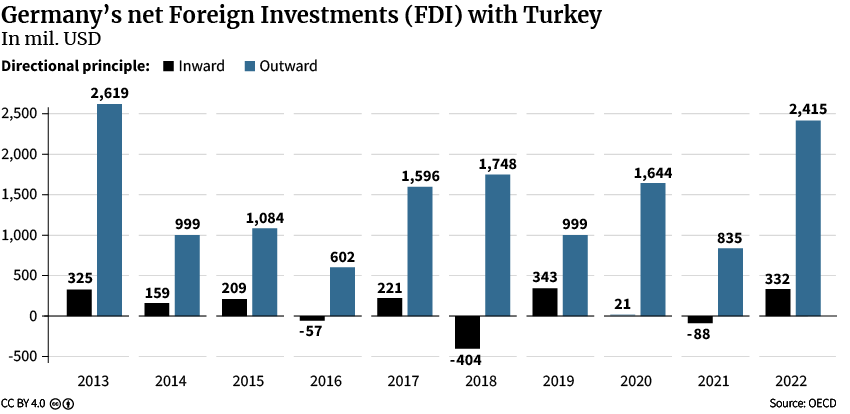

Germany belongs to the group of countries with the highest share of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Turkey. As Figure 7 shows, FDI inflows from Germany to Turkey reached nearly USD 2.5 billion in 2022. By contrast, Turkish FDI inflows to Germany are gradually recovering after a decline in 2018. Turkey attracted from Germany a total of USD 14.3 billion in FDI during the period 2013–2022.

Infrastructure modernisation, market size and demographics are key factors explaining Turkey’s attractiveness to German companies. Conversely, the large Turkish community in Germany is an incentive for Turkish companies to invest in Germany.

Fig. 7: Germany's net FDI with Turkey

↑ To the Table of Contents

Turkey has competitive export sectors that are part of international value and supply chains: The Turkish automotive sector is at the forefront of Turkish exports and technological innovation. Germany was the largest export destination for Turkish car manufacturers in 2023, with exports worth USD 4.8 billion and a share of almost 14 per cent. Meanwhile, total exports of the Turkish automotive industry amounted to USD 35 billion.

The electric vehicle TOGG – the first of its kind in Turkey – is now in serial production. China’s electric vehicle manufacturer BYD announced in July 2024 that it will build a production facility in western Turkey. The country is also a large market for vehicles “Made in Germany”. With numerous highly modern and effective research and innovation clusters, the Turkish automotive industry is preparing itself for the challenges of digital transition (Aydın 2024).

The decision by BYD to invest in Turkey adds urgency to current discussions about a modernisation of the CU with Turkey (Aydın 2020). Expanding the CU should therefore include issues such as the transparency of supply chains and revised subsidy regulations regarding the manufacture of Chinese electric vehicles in Europe (Bastian, 2024).

The Turkish defence industry has developed rapidly over the past decade. Its products – most prominently drone innovation – have frequently demonstrated their military capabilities in different theatres of conflict, including Ukraine, Libya, Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh. The Turkish military industrial complex is increasingly an economic factor and has substantially expanded its export capacity during this period.

Engagement between financial sector firms from Germany and Turkey has been rather limited. Deutsche Bank has operated one branch in Turkey since 1988, while Landesbank Baden-Württemberg has had a representative office in Istanbul since 2015. Aside from that, the promotional bank KfW IPEX-Bank is registered in Istanbul. By contrast, all leading Turkish banks (KT Bank, Ziraat Bank, TF Bank and İşbank) have representative offices and/or branches across Germany catering to the Turkish community and businesses. Even as international investors are gradually regaining confidence in the Turkish financial sector, German banks are not yet prepared to join the queue.

Turkey has been investing in the energy sector for years – several billion euros have been allocated for the expansion of energy infrastructure and technical equipment required for gas exploration. As a recent signatory to the Paris Agreement, Turkey has set itself the goal of achieving a climate-neutral economy by 2053. Accordingly, investments are being made in renewable energies to transition to a carbon-free economy.

All this and a favourable climate make Turkey an attractive market and investment country for international energy companies. This benefits not only domestic companies that build large-scale machinery, but also major international corporations that manufacture high-tech equipment and machinery. Due to its climatic conditions, Turkey has a high potential for natural energy sources such as solar energy, hydrogen, geothermal energy and wind energy.

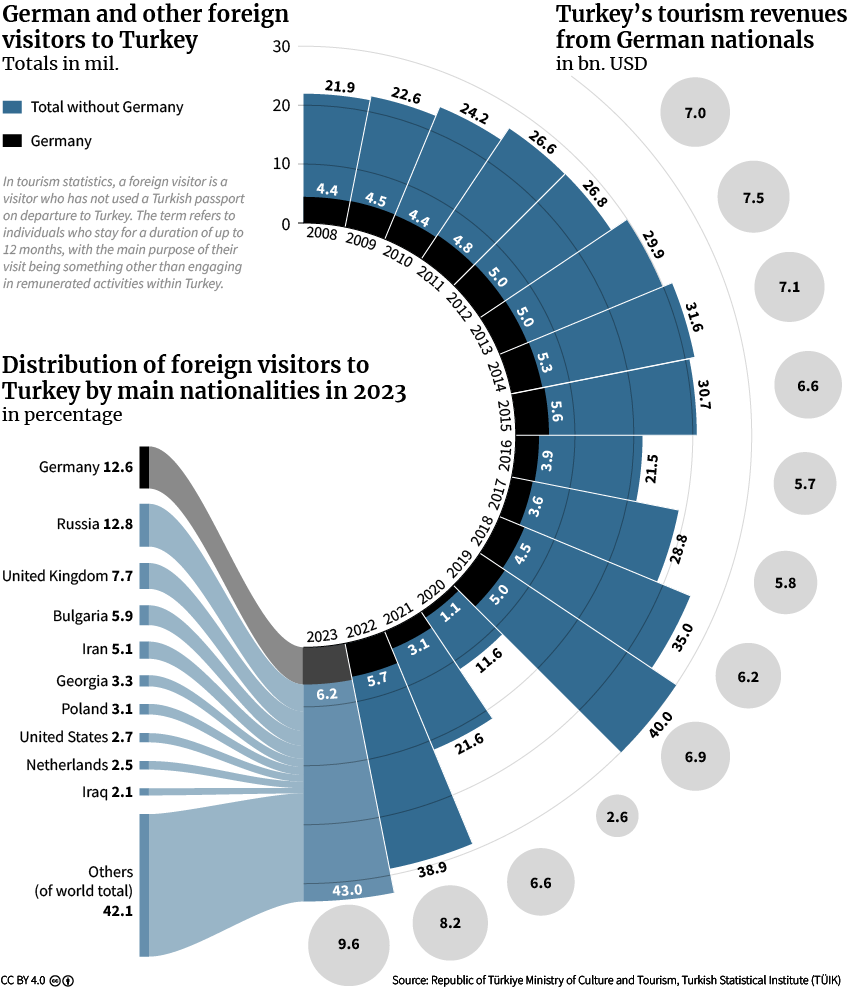

Fig. 8: Foreign visitors to Turkey

It is evident from Figure 8 that tourism plays a significant role in the Turkish economy. In 2022, 5.7 million German tourists visited Turkey, and the numbers reached a record level of 6.2 million in 2023. This corresponds to a share of 12.6 per cent of all tourists who travelled to Turkey in 2023. It follows from such tourist arrival volumes that they contribute a major share of Turkey’s foreign currency revenue.

The textile sector is one of Turkey’s most important economic sectors. It provided employment for nearly 1.5 million citizens as of 2023. Turkey ranked as the fourth-largest global textile exporter in 2022. The Turkish textile industry has succeeded in maintaining and improving its position on the international market thanks to its strong internal dynamics, that is, manufacturing capacity and export orientation. Exports from Turkey’s clothing industry totalled USD 17.14 billion in 2020.

Another important sector is the Turkish construction sector. It has been a major driver of transport infrastructure and residential buildings. However, the earthquake in February 2023, which extensively impacted south-eastern Turkey, tragically illustrated major deficits and corrupt practices in the construction sector.

↑ To the Table of Contents

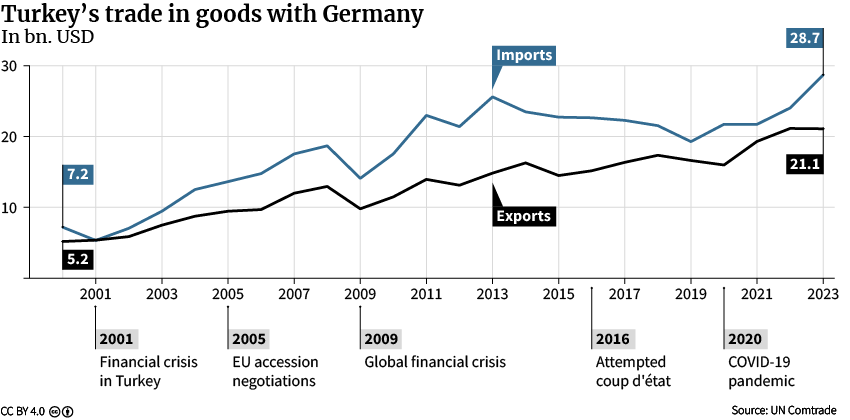

In recent decades, the volume of bilateral trade between Turkey and Germany has increased and diversified. In 2023, it reached a record level of USD 49.8 billion. Turkish exports to Germany totalled USD 21.1 billion, representing a 25 per cent increase compared to the previous year. The volume of Turkish imports from Germany totalled USD 28.7 billion, representing a 33 per cent increase. Both indicators are expected to continue rising in the 2023–2024 period. Despite various domestic (2001) and global crises (2009, 2020), the rising trend of bilateral trade was minimally impacted and recovered quickly.

Fig. 9: Turkey's trade in goods with Germany

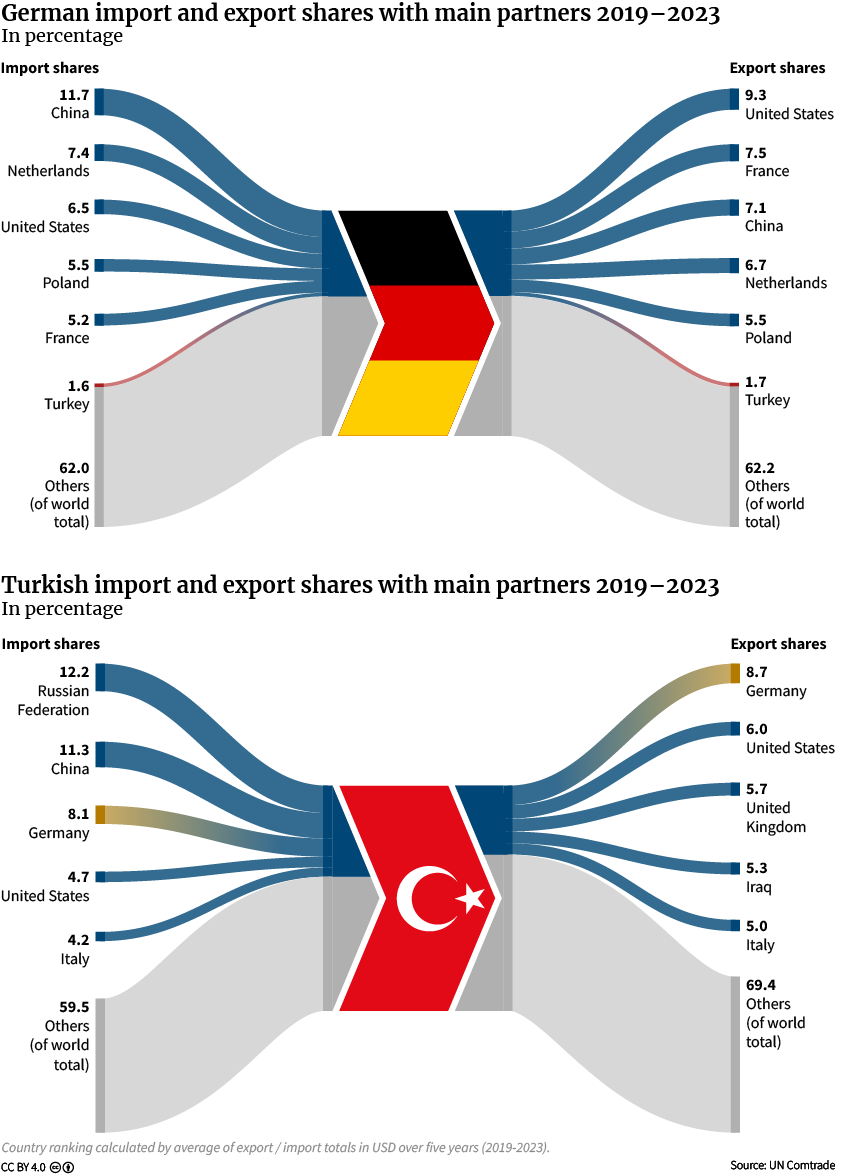

Germany accounts for 8.7 per cent of Turkey’s total exports (Figure 10b) and is the country’s largest export partner. The United States (6.0 per cent) and the United Kingdom (5.7 per cent) follow in second and third place, respectively. Conversely, Russia registered the highest export share to Turkey with 12.2 per cent, followed by China with 11.3 per cent. Germany accounts for 8.1 per cent of exports to Turkey. Turkey’s share in total German imports is only 1.7 per cent (Figure 10a).

Fig. 10a (top): German import and export shares with main partners 2019–2023. Fig. 10b (bottom): Turkish import and export shares with main partners 2019–2023

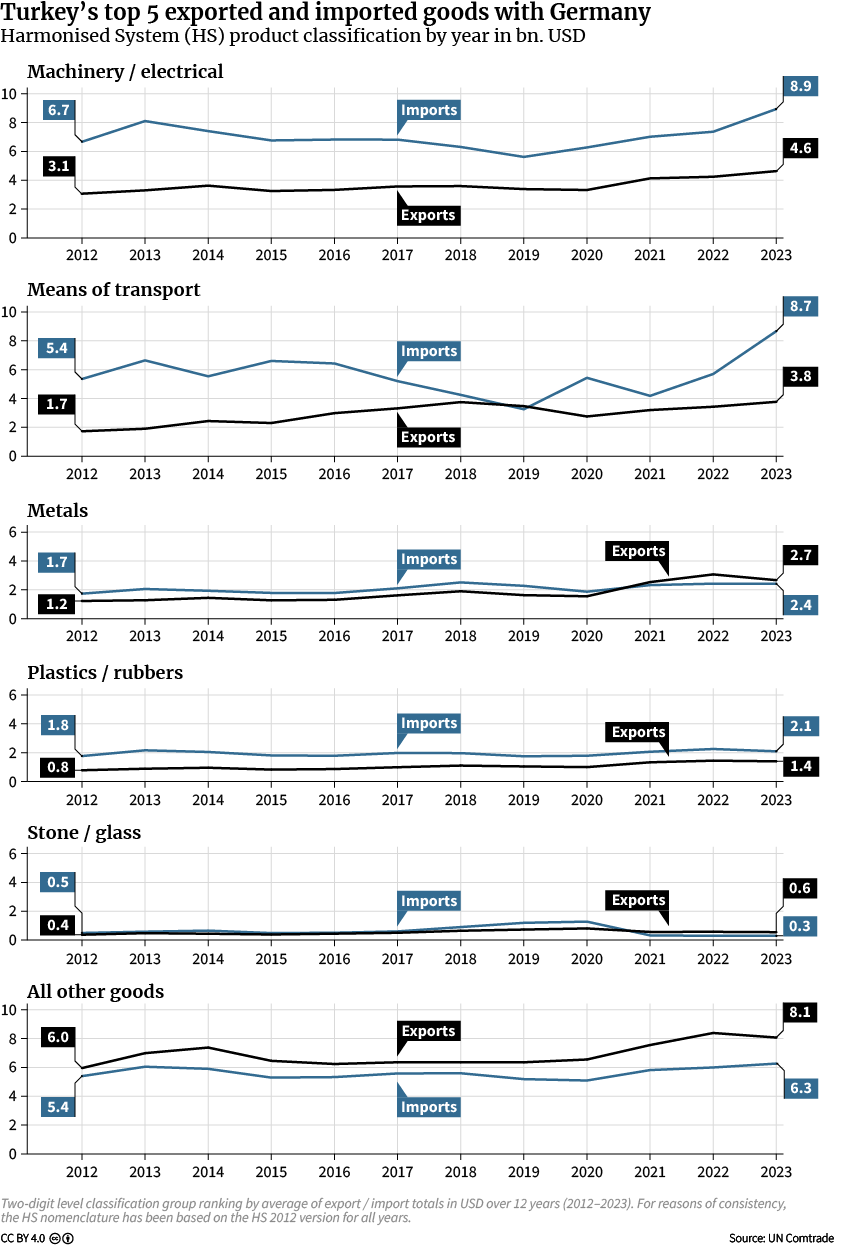

As Figure 11 illustrates, Turkey's single largest import value of trade in goods with Germany in 2023 was comprised of different means of transport (25.37 per cent), followed by machinery, electrical components and mechanical appliances (23.08 per cent).

Turkish exports to Germany primarily include textiles, leather goods and motor vehicles, but increasingly also food and machinery. Figure 11 highlights similarities in the sectoral composition of Turkey’s exports to Germany. The difference concerns lower volumes of exports compared to imports. Turkey’s single largest export value of trade in goods with Germany in 2023 was comprised of different means of transport (16.4 per cent), followed by machinery, electrical components and mechanical appliances (15.25 per cent).

Fig. 12: Turkey’s top 5 exported and imported goods with Germany

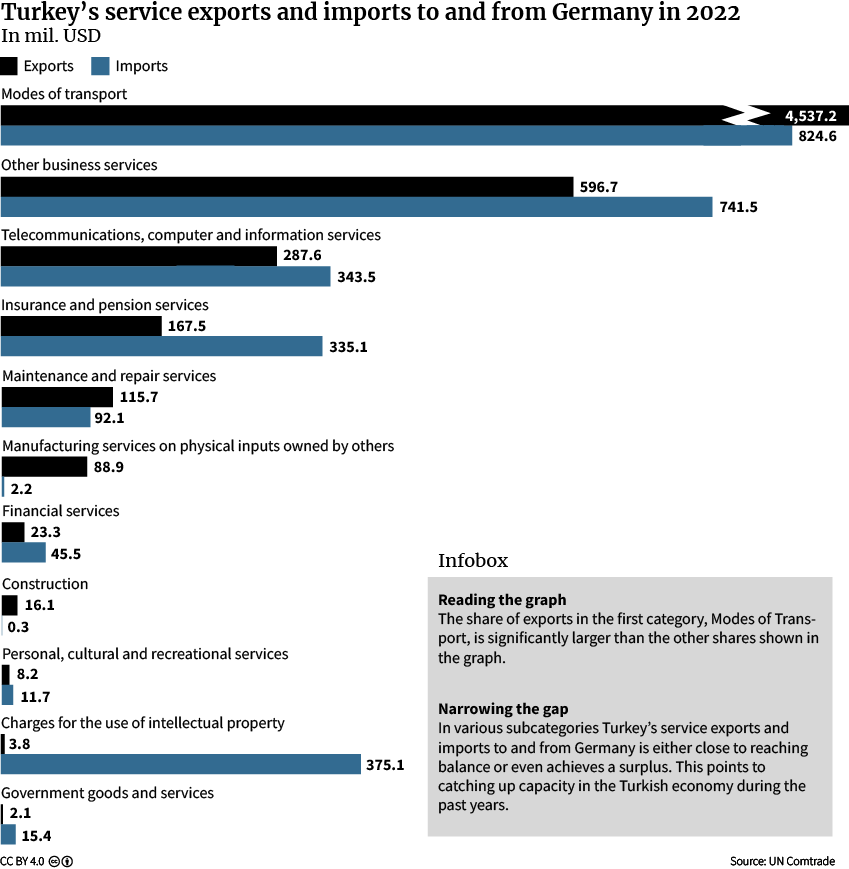

Commercial trade between Germany and Turkey is generally positive, rising and broadly represented across various industries and services (see Figure 13). There is one notable temporary exception, namely means of transport during 2019 and 2020. This was the result of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 12).

Fig. 13: Turkey's service exports and imports to and from Germany in 2022

How can Turkish-German bilateral economic relations and cooperation develop further in the coming years? A key factor will be Turkey’s medium-term economic stability. Turkey’s and Germany’s green energy transformations are also crucial for such economic interdependence.

At the European level, the continued harmonisation of legislation with EU norms and regulations – in particular the modernisation of the CU – will be important milestones in that endeavour.

Opening new channels of commercial exchange and foreign investments is advocated in both countries. Towards that end, bilateral cooperation will need reliable political frameworks in both Ankara and Berlin that overcome current transactionalism. In other words, the rule of law should be re-established in Turkey, and trust-building mechanisms should be expanded with Germany. Increasing institutional cooperation in the areas of energy and “green transition” can lay the foundation for this. Bilateral cooperation in the earthquake reconstruction efforts that followed the devastation in southern Turkey in February 2023 is part of such trust-building mechanisms.

↑ To the Table of Contents

A significant opportunity for economic cooperation rests in transnational linkages, which are reflected in the sizeable Turkish community of more than 3 million citizens in Germany and several million people in both countries with a German and/or Turkish background. This has provided a substantial pool of labour for German and Turkish companies in both countries. Further opportunities are opening up in the area of training and recruiting, especially among medical and nursing professionals. These are important factors that must be taken into account in the event of a revision of the EU-Turkey Refugee Agreement from 2016, given the need for skilled workers in Germany (Aydin, 2024).

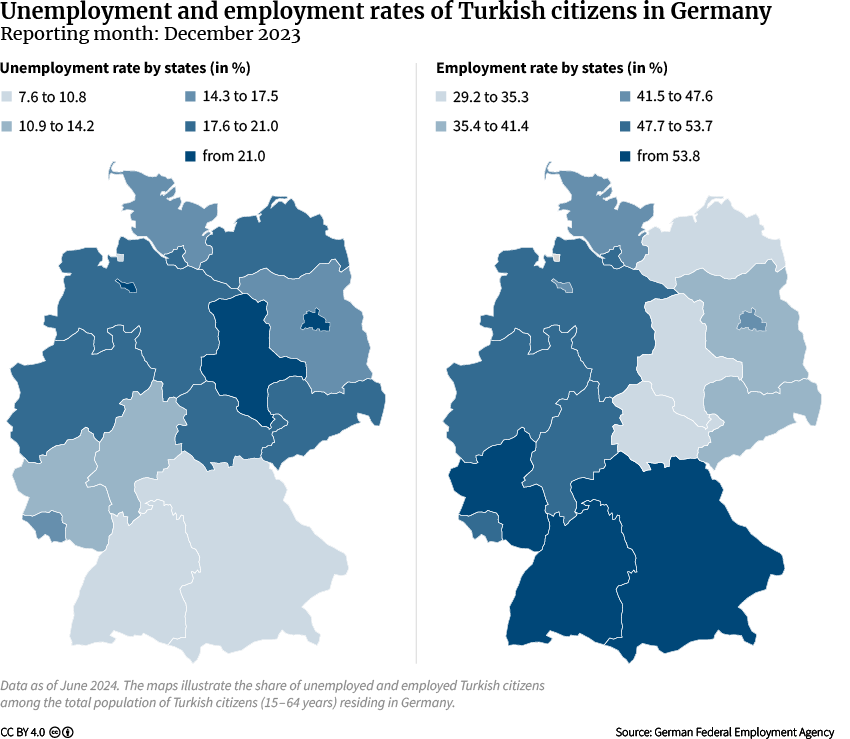

Figure 14: Unemployment and Employment Rate of Turkish Citizens in Germany

Germany is home to a sizeable Turkish diaspora, comprising more than 3 million permanent residents with roots in Turkey. Of these, 1.48 million are citizens of the Republic of Turkey, according to available data from 2022. Additionally, over half a million Turks in Germany have dual citizenship (data from 2021). This diverse community has significantly contributed to the development of the German economy. Since mid-2015 there has also been a new wave of Turkish migrants who are highly skilled and well-educated and contribute to the health and IT sectors in Germany.

The unemployment rate of Turkish nationals in Germany is higher than that of their German peers. This is not only a curse but also a blessing. It points to untapped potential in terms of labour market integration and filling skills gaps.

As Figure 14 above illustrates, the employment and unemployment rates of Turkish citizens in Germany reflect north-south and east-west differences. In that respect, the picture is not that dissimilar when compared to German citizens and their employment status. However, we can infer from Figure 14 that the unemployment rates of Turkish citizens in Germany are considerably higher across the country than those of their German colleagues.

Turkish-German business associations coordinate bilateral trade and economic collaborations. Approximately 75,000 entrepreneurs with roots in Turkey – some of whom are German citizens and others Turkish citizens – employ approximately 375,000 people in Germany and realise an annual turnover of approximately EUR 35 billion.

↑ To the Table of Contents